Elements of Photographic Language

A proposal with 7 categories and 59 elements that can help to better understand the language of photography.

A photograph contains numerous meanings, that is why it is a polysemic phenomenon, and to unravel them the first step is to recognize your own grammar. It is a specific vocabulary with a specific syntax. In addition, it has its own way of articulating this particular language. We could call style to the way in which each photographer uses this visual language. It is a good start to have an overview of some of the elements that make up this language that is useful both for those who take a photograph and for those who analyze it.

First it is worth making a great division: We propose to start with seven large groups or categories. Of course they are a starting point and more groups can join.

1. Photographic Attributes

It is properly about those elements, broadly speaking, typical of the image in general and the particular attributes that make an image be considered a photograph with its own morphology, characteristics, syntax and grammar. They are the general attributes ( iconographic ) to the particular ( photographic ) where we could include distance, framing, light, focus, time, movement, etc. These unit attributes help us determine the components of the image that is read. To a certain extent it is like the ingredient list on a plate and they are the denoting elements of the image. How they are combined has to do with our next group: composition.

2. Composition

All photography contains elements that are articulated, organized in a specific way, that have a certain design and composition. Then, it is necessary to include some evaluation elements that allow us to analyze a photograph as it is made from the point of view of organizing its forms. Here we will find elements such as proportion, rhythm, etc.

3. Continent and Content

In every photograph there is a continent (the photo itself) and content (what is pictured). The continent implies the format: If it is a daguerreotype, an ambrotype or an electronic image, with what type of instrument it was made. It matters because different teams may have what Vilém Flusser calls “Program”, that is, the limitations or characteristics of the medium. For example, a medium format dual lens reflex camera will forcefully generate a 1:1 ratio frame, that is, totally square, and that will force the photographer to make certain specific decisions given the peculiarity of the aspect ratio in the frame.

The content makes us reflect on the photographic motif, if it includes people, what is their speech and how the visual narrative has been made.

4. Style and Gender

The genres help us understand a set of canons (rules) with which an image is read. Thus, it is not the same to read an urban portrait than a street photograph, a found photograph than a created one, and so on. Understanding this set of conventions makes it possible to define whether it is a canonical image (that is, it follows the rules of the genre to which it belongs or if it disrupts them), contradicts precepts or adds new elements to a genre, such as what happened with Richard Avedon when he added movement to static postwar fashion photography.

5. Authorship

The author of a photograph is not always known. For example, we often ignore the name of the visual creator in most advertising photography. However, valuable contextual information is obtained by knowing who the author is, if he belongs to a certain school, with what other photographs he is related, etc. In hermeneutics this means knowing what is said but also who has said it. As Luis Enrique de Santiago Guervós says “It is not simply a matter of understanding the meaning of a text, but above all of capturing how that text was produced, what is the genesis of its creation.”

6. Intent

It helps to understand the author’s purpose. Do not forget that to read a photograph you need what Fiedrich Schleiermacher called “… the art of correctly understanding another’s speech.” This can lead us to try to better understand the meaning of the work, as well as assess how it is disseminated (distributed) or how it is received. Now, we must not forget that it can also happen that the photographer has a certain intention, but the observer interprets the image in a different way than the one the author was looking for. Nor is it wise to fall into intentionalism.

7. Semiotic Elements

The reading of photography as a sign inserted in a system of signs can be enriched if we take the semiotic trichonomy of Charles Sanders Pierce trying to understand photography from the iconic point of view, as a sign (or set of signs), in a symbolic terrain and its role as a trace of a physical event ( index ). It is useful to refer to our Minimum Guide to Photography and Semiotics.

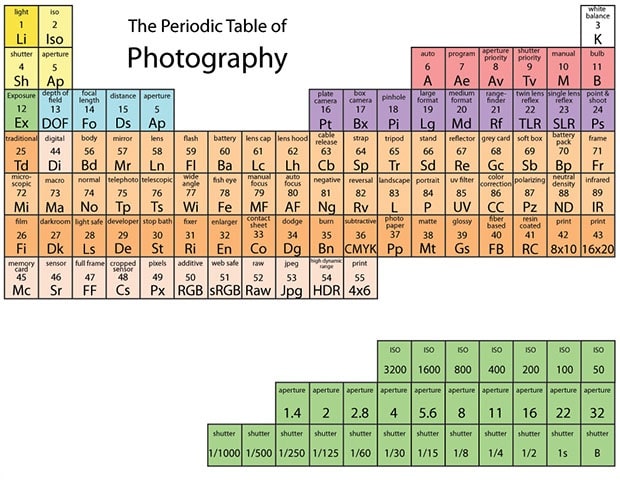

The table of the elements of photographic language

These seven groups can be broken down into 59 individual elements. We propose the following table inspired, of course, by chemistry and taking as a first starting point the work of Javier Marzal Felici and Cynthia Way of the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York.